Siza: Notes on Nature

Barry Bergdoll

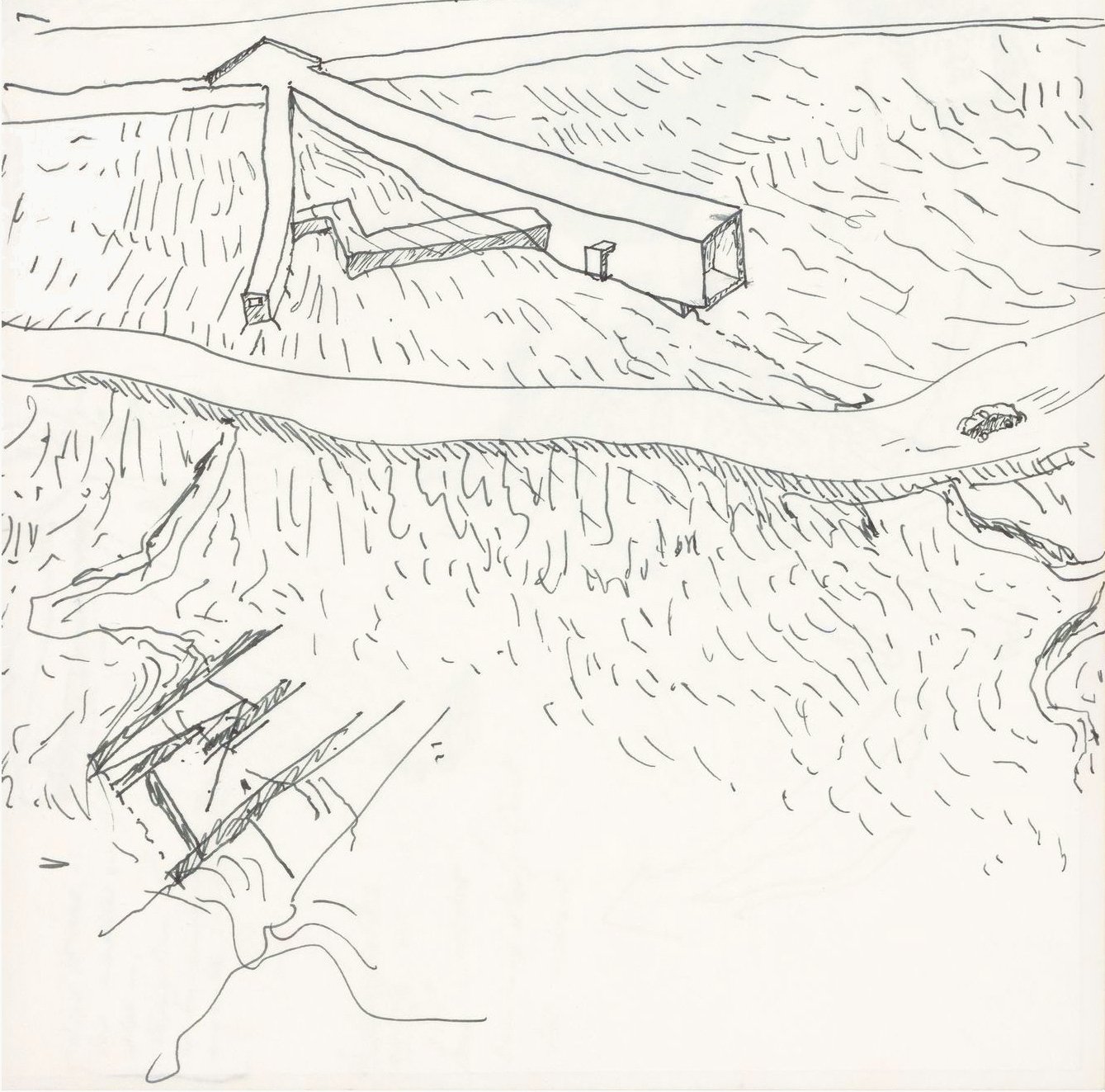

Álvaro Siza. Sketchbook 338, August 1992 [detail]

©Álvaro Siza fonds CCA

.... ..[Texto original em Inglês]....

“A significant moment of encounter between pragmatics and poetics at the genesis of each of his projects.”

One is struck from the very first sentence that this is at once a volume of reflections that is quite unlike most statements of that time, even as it resonates with the longest traditions of architectural thinking and theory. Indeed, the idea of respect for tradition and a refusal of the avant-garde fetish of originality is characteristic of Siza’s position and of his work from the outset as he began work with Fernando Távora. That first line – “Architecture has no meaning unless in relation to NATURE” – might be read either as a prediction of the environmental and climate crisis that is fundamental to our existence now two decades after these lines were first printed in Italian (translated from the Portuguese), and to the very opening lines and argument of the Abbé Laugier’s 1753 Essay on Architecture. Laugier’s collection of six texts on building, landscape design, and the city is often considered a very starting point of modern architectural thought, a text that was at once a fundamental revision and yet a reflection on the oldest book on architecture we have, that of Vitruvius. But Nature for Siza is neither a metaphor for Enlightenment reason, nor of its child structural rationalism, as in Laugier. For Siza is as much interested in human nature which for him has as much to do with our inner being as with some higher disembodied reason. He speaks of “tough intuition” and in another passage of “instinctive wisdom.” The human animal is more than a reasoning brain, calculating loads and spans, she or he is an inhabitant of a complex world of sensations and reactions that draws much from the unwritten and the unspoken, the drawings are somewhere between the unspoken and the utterance, I guess.

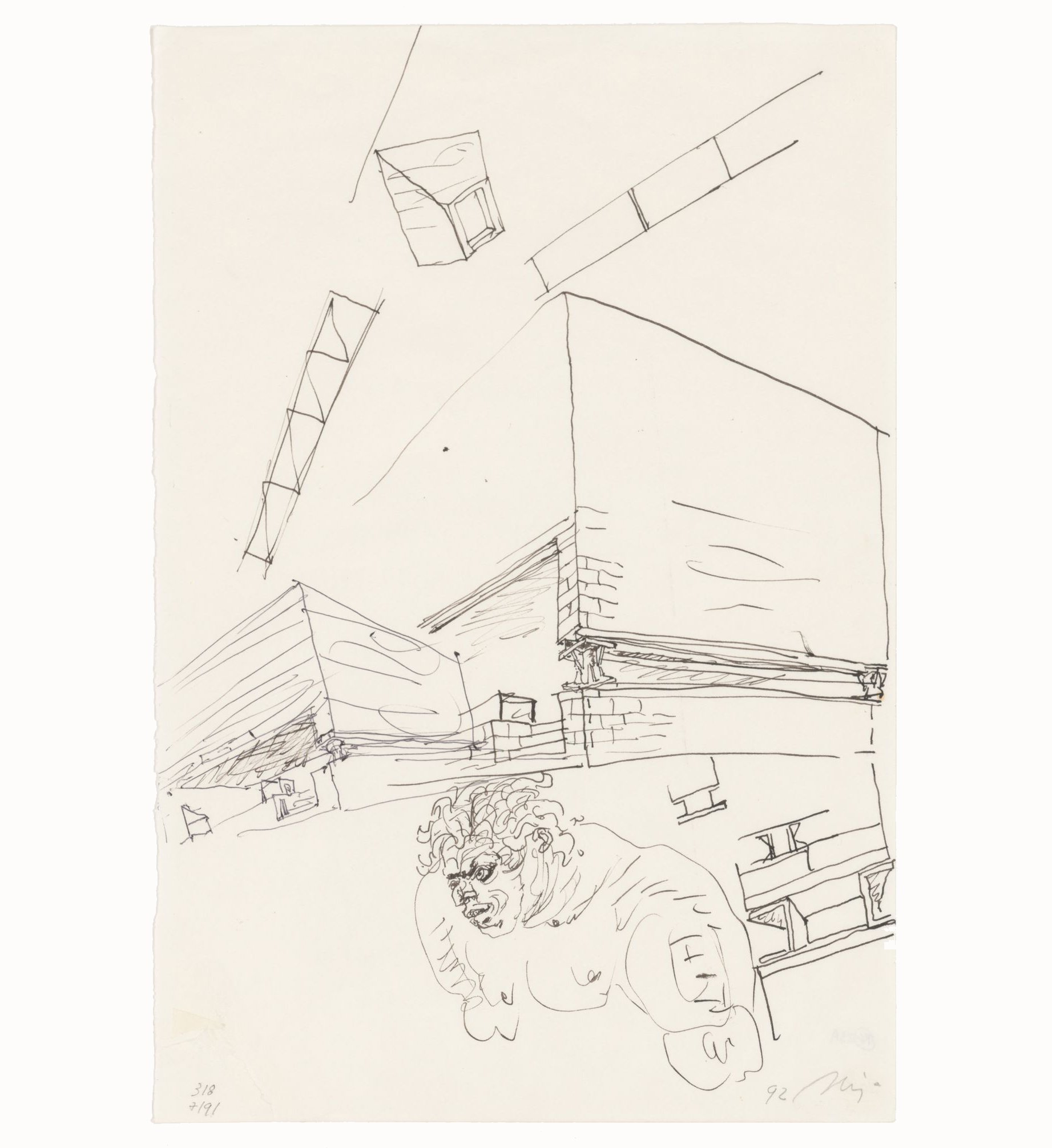

Álvaro Siza, Perspective sketch for Centro Galego de Arte Contemporânea [Galician Centre of Contemporary Art], Santiago de Compostela, Spain, 1992

©Álvaro Siza fonds CCA

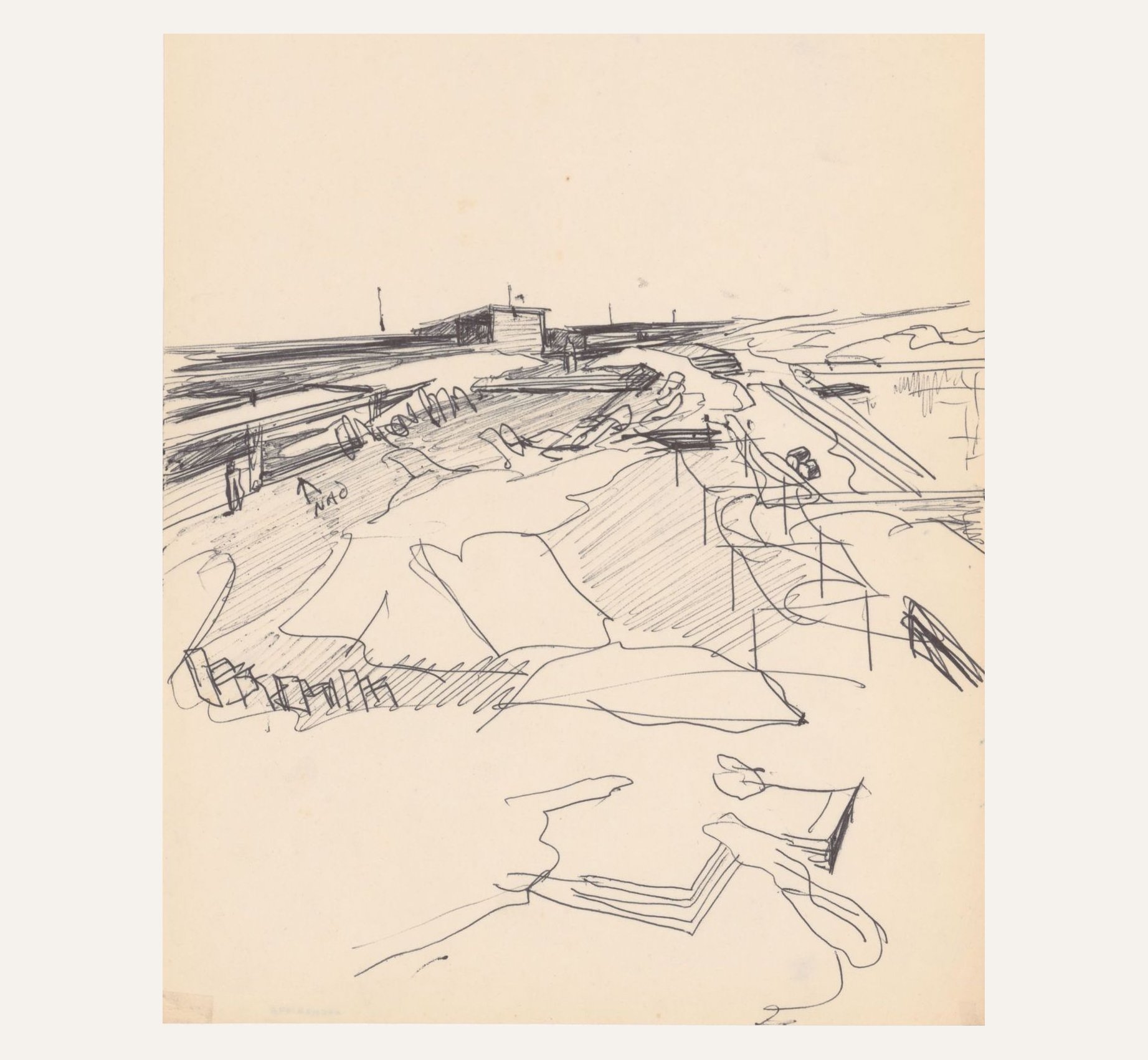

Nature, for Siza, as he writes and draws in such symbiotic harmony, is more about the nature of the site, the inhabitation of the site, of the terrain, of the place as it is about an abstracted notion of Nature in the 18th century or the ecological consciousness per se as it developed over the decades of his own early practice. It is trees qua trees rather than trees as metaphor for structure, and its is a sense of place that is at once as pragmatic as Vitruvius notion that the choice of site is the first skill and contribution of the architect and something that transcends any pre-lapsarian nostalgia. Nor is it simply a pragmatic relationship to resources, to a healthy respect for solar orientation, for water resources, or prevailing winds as in Vitruvius’s first book. Siza’s nature is also the poesis of the site, embodied in the story of Fernando Távora’s laconic analysis of the challenge of building the Boa Nova project for his home town of Matosinhos that first brought attention to Siza’s design genius. “The building should be here” he said of the difficult site wedged between the crashing waves of the Atlantic Ocean and the passing traffic. “During these initial works,” Siza relates as the book veers into an autobiographical passage relating a significant moment of encounter between pragmatics and poetics at the genesis of each of his projects, “an irrepressible and prevailing idea began to blossom, that architecture does not end anywhere; it goes from object to space and, by consequence, to the relations among spaces, until its encounter with nature.” He continues with a line written in the 1990’s but even more powerful today: “This idea of continuity, which may also exist among all its eventual dissonances, is currently in crisis, and natural locations are beginning to suffocate, even though it is quite clear that architecture has no meaning unless in relation to nature.”

Álvaro Siza. Sketch for Piscina das Marés [Ocean swimming pool], Leça da Palmeira, Matosinhos, Portugal, 1961-1965

©Álvaro Siza fonds CCA

Continuity is perhaps the concept that ties together all of Siza’s commitments, the very ethos of his practice, for it applies to the reciprocal relations of building and site, of architecture and nature, but also of architecture and human perception of time, and of the designing impetus of the architect in relationship to the history of architecture. The reflection on the nature of influences – a word I always prefer to replace by the more active interests – on Frank Lloyd Wright, on Aalto, on Breuer – is something that should be very instructive for students of architecture. Siza’s is a conception of the human as part of nature, not in dialogue with nature. Human activity is in dialogue with nature such that Siza can speak beautifully of intuiting the site to find the precise location, the place that is, as he writes “ready to receive geometricity.” As you can see the texts as much as they seem as short as prose poems, are also liked compressed soil, filled with richness, potent not only for understanding Siza’s practice over many decades, but for undertaking architectural design or architectural criticism and history today. What is beautiful in this volume is the complete absence of photographs of the finished buildings, partly perhaps because each of the projects is so well known, but also because the book is about the hand and mind of the architect before construction begins, the choice and placement of Siza’s drawings integrated with the text is exquisite, the two work in symbiosis and continually reinforce this search for continuity. Excuse me for a moment to bring the perspective here of the art historian, but it was this symbiosis of text and reproduced drawings that made me understand – perhaps even intuit in Siza’s words – the profound meaning of the frequent extension of Siza’s thin but forceful drawn lines that form the building’s volumetrics into the larger space of the sketchbook sheet – or are they projected from that space to form the building… Just as the buildings are about continuity with nature, atmosphere, and site… and it made me reflect on the fact that Siza – in part inspired perhaps by Le Corbusier’s graphic demeanor – prefers over and over again perspective views from above or below the horizon line, rarely asserting the canonic Renaissance two-point perspective with its insistence on the horizon, an artifact of human optics rather than of nature. It is this decentering that marks already a fundamental continuity between nature and architecture, between the site and the designing builder.

Álvaro Siza. Sketches for Piscina das Marés [Ocean swimming pool], Leça da Palmeira, Matosinhos, Portugal. 1961-1965

©Álvaro Siza fonds CCA

As a historian, and one who has taught many students who have passed through this school [Columbia GSAPP], I am especially drawn to reflect on Siza’s words about the history of architecture, about great masters, about the process of accumulating influences over the decades between study and the mature work of an architect always striving that strike me as a way to close this small appreciation of Siza’s huge contribution to architecture, captured in this exquisitely modest volume. The passage comes after mentioning his readings of Giedion as a student and his joint admiration of Alvar Aalto and of Frank Lloyd Wright: “I believe that the meaning of apprenticeship, in architecture, is precisely to broaden one’s range of references. At the outset there is always a charismatic figure that captures our interest (and here I like the shift from influence to interest), and consequently has decisive influence on us…. The articulation of these influences is an unrepeatable act of act of creation. An architect works by manipulating memory, there is no doubt about that, both consciously and, most of the time, subconsciously. Knowledge, information, the study of architects and the history of architecture tend, or should tend, to be assimilated until they fall into the oblivion of the unconscious or subconscious.”

Álvaro Siza. Spread 002-003 from Sketchbook 256, August 1987.

©Álvaro Siza fonds, CCA. AP178.S2.256

Imagining the Evident / Álvaro Siza

The referential book by Álvaro Siza on his own work, in its first English edition. Describing some of his projects, his expectations and struggles, references and decisions, this book is a fundamental contribution to the understanding of Álvaro Siza’s architectural thinking.